It’s been a minute since I wrote a blogpost focusing solely on gold. Now is a good time.

Many investors struggle to understand the benefits of investing in gold and what role gold can play in a portfolio. But gold has been an important investable asset for millennia. While it is no longer a medium of exchange due to the dominance of fiat currencies, gold can be a strong diversifier in a buy and hold portfolio, as Harry Browne’s famous Permanent Portfolio indicates. In that portfolio, Browne includes a 25% allocation to gold, equal to that of stocks, while the remainder of the portfolio is in cash and long-term treasuries.

The presence of gold in the portfolio, and the reduced exposure to stocks, is one of the reasons that the portfolio experiences low drawdowns relative to other buy-and-hold portfolios. In the worst 20 quarters of the stock market since 1967, for instance, gold’s return was positive three-fourths of the time:

Indeed, since the beginning of the 21st century, gold has outperformed both stocks and bonds:

However, we do not advise holding gold indiscriminately at all times. Instead, we utilize momentum methods to invest in gold when it is in an uptrend, and to invest in other investable assets when it is not. In our Gold Long Trend model (GLTR), we hold gold ETFs about half the time. The other half of the time we hold ETF positions in our all-asset A-GEM momentum model. Last year that meant holding U.S. growth stock ETFs at times, as both those ETFs and gold ETFs had a strong year.

In this backtest from January 1999, our GLTR model outperforms all of the following: gold itself, the S&P500, and a balanced portfolio of stocks and bonds:

Note: see the disclaimer at the end of this blogpost for information about the limits of backtesting.

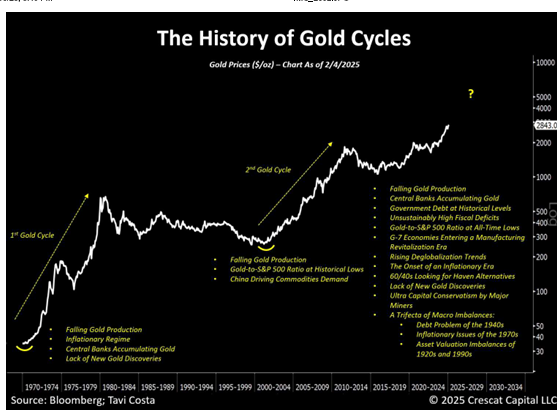

Gold is notoriously difficult to trade because it can spend long periods of time flatlining or declining, even if it does have long bullish periods. This is a year-by-year continuous futures contracts chart of gold prices from 1970 to the present:

Gold had a roaring 1970s related to certain fundamental factors like inflation and permitting U.S. citizens to old gold other than through numismatic coins. But then gold went dormant for almost two decades in the 1980s and 1990s as inflation abated and geopolitical risk declined.

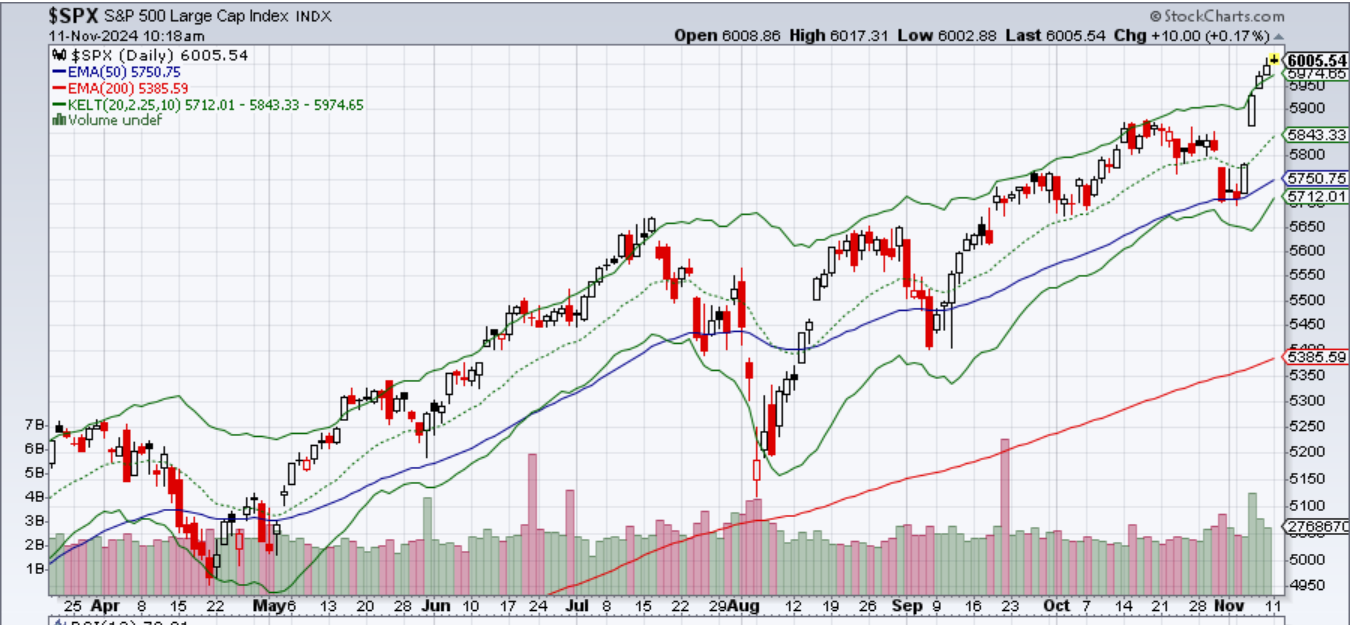

But in the 2000s, after 9/11 and the rise of China as a consumer of world commodities, gold had another heyday, that is, until the 2010s when disinflation and zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) held firm. That began to change, however, in the months before the COVID pandemic began:

This is a monthly chart of the same gold instrument showing a breakout of a price consolidation that occurred in the months before the COVID pandemic. In that respect, I wrote about gold’s rise during this time as our momentum models shifted into gold and long-term U.S. treasuries before the pandemic selloff in equities here and here.

Eventually, another consolidation pattern would emerge from 2021 until an indisputable breakout in 2024, a breakout that continues to this day. Additionally, that most recent consolidation bears the hallmarks of a bullish inverse head-and-shoulders pattern.

Of course, we always follow our models, and momentum works on any asset that can experience times of trending, but there are fairly obvious reasons that gold prices have been rising. A firm I follow, Crescat Capital, has been one of the best sources for understanding the rise in gold prices.

Of note in Crescat’s chart are explanations for why gold experienced bull markets in the 1970s, the 2000s, and now. The list supporting the current rise is three to four times longer than that supporting the prior bull markets. Where in the past falling gold production, inflation, and demand from central banks and China were in place, now the same factors are in place, plus additional geopolitical risk and major fiscal deficits.

To be more specific, central bank gold buying has doubled in the last ten years, as an excellent blogpost from Callum Thomas indicates:

Thomas further notes that these fundamental drivers of higher gold prices are not changing anytime soon. Additionally, he notes that the retail investor has yet to come on board to gold investing, suggesting that there is much room to run, just as in the 1970s and the 2000s.

For these reasons, we believe our GLTR model is well-positioned to take advantage of another multi-year bull market in gold.